This week, Ben learned about how to map out arguments using Toulmin diagrams. You can learn more about how they work here, here, here and here.

In an earlier entry, I talked about the beauty of the sports argument. These types of debates are popular and interesting because you’re not really debating who the better player or is, you’re debating what it means to be a better player.

To refresh your memory, here’s an example in the form of an informal argument:

Premise 1: Player X is superior in various areas of game play

Premise 2 [hidden premise]: A list of criteria that the arguer thinks makes someone a superior athlete that matches the characteristics of Player X

Conclusion: Player X player is the superior athlete

Now because the first premise is usually not debatable (since it’s related to checkable sports statistics), the real argument stems from that hidden premise. This premise actually makes a claim about how the world works (or at least the sports world) and once you get into complex arguments with many debatable claims, you are better off mapping your argument with what’s known as a Toulmin diagram, rather than just using words.

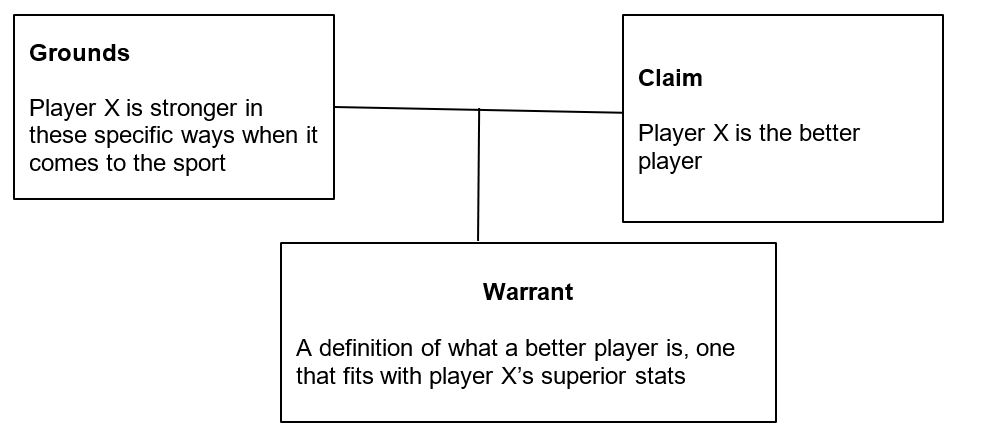

For example, my rough sketch (sorry for the crooked lines) of that sports argument as a Toulmin diagram looks like this:

The statement in the box labelled “Warrant” is the same as the hidden premise in my informal argument, and in a complex argument that claim can be challenged, causing the argument diagram to branch out. For example, if my definition disregards the role of team accomplishment (Player X could be successful due to team factors like a strong offensive line and great defenders) someone could object to my warrant and I would have to respond to that objection.

This might seem like overkill for my simple sports argument, but Toulmin diagrams can help capture the arguments in many of the conflicts we are dealing with in real life.

For example, today we are moving headlong into changes in terminology regarding how we see, understand and solve issues having to do with race and racism, such as a new distinction between being “non-racist” and “anti-racist.” Has our fundamental understanding of what is right and wrong regarding race really changed? I would say no. So why are people who were comfortable treating others as equal, regardless of race, now saying that Hamilton’s intentional colorblindness is no longer a welcome political statement?

It is because we are experiencing changes to hidden premises regarding how we get to the equality we all long for, and what parts of the world need to change in order to do so. If we were being clear about the subject, that’s where the real conflict lies, rather than over the simple question (with an obvious answer) of “is racism bad?”

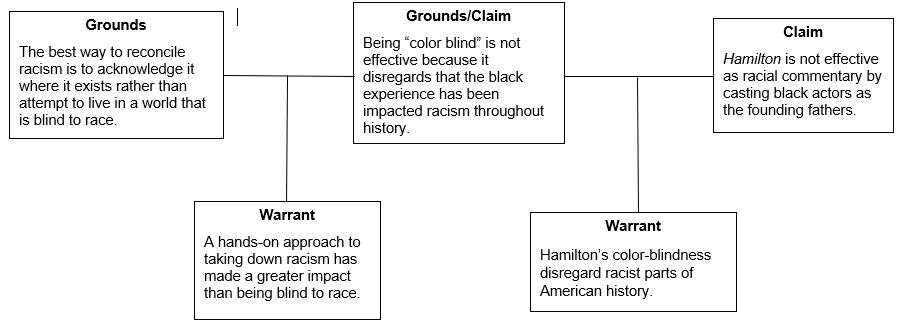

The debate is not over whether we should end racism, but what is the best means to do so. The complexity of even a simple argument, like one over Hamilton, is best laid out in a Toulmin diagram like the one below. (If you’re not familiar with the controversy over Hamilton, hopefully this will explain it for you).

Our arguments tend to get stuck when we assume that things like grounds and warrants are facts rather than their own debatable claims which cause people to think there is no way the person they’re arguing with could be right since they are disagreeing with what you believe are facts.

But because most points in this argument are debatable, people can challenge them using an objection or an objection to that objection (called a rebuttal).

For instance, in the above argument someone might object to the claim that creating a color-blind society is not the best way to fight racism by, for example, claiming new generations could live without prejudice if younger people are brought up not assuming anything about other people based on their race. Since this objection is also a debatable point, someone could try to rebut it with an analogy that claims gay rights came through activists embracing their gay identity and asking society to accept it, and so forth.

You can start to see how diagraming our arguments lets us see what we’re actually arguing about to better understand debates that are as multi-faceted as they are important.

Leave a Reply