Back when I started my Degree of Freedom project, I heard word of a film in the making that would center on MOOCs which I later learned had branched out from that subject to more broadly discuss the current state of higher education.

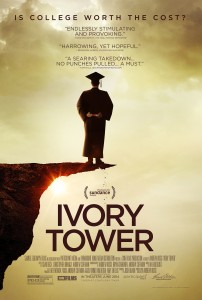

I’m guessing that Ivory Tower, a documentary currently doing the rounds at independent cinemas (and likely to be showing up on cable soon – given that it was produced by CNN), was the work I had heard about. The film is directed by Andrew Rossi (whose previous film, Page One: Inside the New York Times, looks at crises unfolding at another great American institution) and provides a solid encapsulation of what now serves as the conventional explanation for today’s crisis in higher education.

I say “explanation,” but we’re really talking about a range of issues that all add up to the problems that have been the subject of Monday explorations at this site: the skyrocketing cost of earning a college diploma and what (if anything) MOOCs or other technological solutions might provide to ameliorate (or even solve) the challenge of college pricing itself out of reach the moment a degree has become the most important ticket to a decently paying job.

The issues Rossi tags as causing college to become the most inflationary product sold today include:

- Increasing competition between prestige colleges and universities who must all have departments staffed to offer degrees in every major subject, housed in state-of-the-art buildings (which include classrooms, research facilities and luxurious high-tech dormitories) where students can also enjoy “gold-plated” amenities like restaurant-quality food, swimming pools and – everyone’s favorite example of excess: the proverbial climbing wall

- The bloating of college administrations who oversee ever-more ambitious building programs, much of them financed through debt or endowments that have both boomed and busted with the ups-and-downs of the stock market over the last several decades

- A cutback in state funding since the 1980s that has led schools to close the gap between ever-increasing costs and decreasing subsidies through jacked-up tuition financed by ever-increasing student debt

Rossi is careful to not point a finger directly at any one suspect (a wise move, given the number of players that have gone into today’s educational cost crisis), although the list above does lead to a set of people (profligate administrators and stingy legislators) more suited for the villain role than other players (like students and faculty).

Not that the latter don’t come in for their share of criticism, especially in discussions of the quality of education one buys for the huge sums colleges charge today. For example, the film spends a fair amount of time documenting the drinking and debauchery scene at Arizona State University (ASU – voted by Playboy Magazine as America’s #1 party school) as well as the tendency for professors to earn high student ratings by making it ever-easier to pass their classes.

However, the overall sense of the film is that these students and academics are being shortchanged by a system in which higher education has become big business interested in winning customers (students) and keeping them happy by giving them four years of unsupervised luxurious living while placing minimal demands on them (academic or otherwise). And given how few of these students actually manage to graduate in four years (less than a third at public universities); it appears that the system is doing nobody (least of all the students it supposedly indulges) any favors.

I’ve always been a fan of the efficiency of the documentary format in being able to cover an argument with a wide range of voices. And given the complexity of today’s educational industry, such a range of voices was welcome when I sat through the film last week (not to mention fun, given that a number of those voices – such as Wesleyan President Michael Roth and Dale Stephens of Uncollege – have made appearances on the Degree of Freedom podcast over the last year).

But the documentary (especially in the Post-Michael-Moore Age) also tend towards an overuse of visual cues to help viewers better separate good guys from bad. Thus scenes at small schools with highly focused purposes (such as Deep Springs College in Death Valley with an enrollment of 26 male student/farmers, or Spelman College which has served African American women since the 1880s) are brightly lit and narrated by attractive thoughtful students, while ASU scenes mostly feature students chugging vodka and punching each other out at pool parties.

The longest segment in the film, which documents the angry protests which followed the decision by Cooper Union in New York to start charging tuition for the first time in its history, comes the closest to pointing fingers, with students accusing a befuddled administration of betraying the school’s founding principles while data regarding that administration’s profligate borrowing and incompetent investment activity ran as background graphics.

This is not to say that the leaders of Cooper Union did not make appalling choices (including investing borrowed funds into hedge funds that crashed and burned in the 2008 financial crisis). But using Cooper Union as an exemplar leaves the impression that if dopey administrators would just stop spending and state legislators could bring themselves to allocate like they used to, then professors (portrayed in the film as critics of excess) could get down to teaching students undistracted by pool parties and rock gyms.

But what if educational budgets cannot be balanced by downgrading unnecessary luxury, ending expansion projects or replacing bathroom fixtures with low-energy bulbs? Would those academic critics pitch in to determine which departments a college or university no longer needs to get along? And who are those expensive research facilities being built to serve if not students and professors who are attracted to teach or study at a school specifically because it provides the ability to research subjects in depth – regardless of how much those opportunities costs to deliver?

MOOCs make an appearance towards the end of the film when the State of California’s brief flirtation with Udacity is portrayed as a desperate attempt to use technology to solve many of the crises plaguing the nation’s most extensive (and expensive) state higher-ed system.

The story the film tells is familiar. When MOOCs had reached their peak hype, California Governor Gerry Brown reached out to Udacity founder Sebastian Thrun to pilot some remedial programs on the San Jose State University campus. But after faculty protests (including complaints by SJSU philosophy professors reproduced in Ivory Tower) and dismal results from the pilot, the program was shelved and MOOCs moved from “solution” to “curiosity” in subsequent discussions of how to reform higher education.

The problem with Ivory Tower’s presentation of that story is not what it includes, but what it leaves out. For example, even as the Udacity pilot (which was meant to see what types of face-to-face tools could best supplement MOOCs, rather than serving as a John-Henry style match-up between MOOCs and classroom instruction) played out, another project that licensed edX content for use in a blended learning environment within SJSU was proving quite successful. (Later scenes in the film display significant optimism over the potential for such learning programs that mix MOOC content with classroom instruction.)

But it was this very edX licensing that got the SJSU philosophy department up in arms, rather than the use of Udacity courses to teach remedial math. And at least Udacity was ready to stop selling a solution that did not seem to be working, unlike many other educational programs – including whichever ones allowed students to get into a state college without knowing math – that seem to go on and on, regardless of their results.

In short (and unsurprisingly), those who know the story behind the story (with regard to MOOC experiments in higher education or any other educational reform) see a far more complex world than the one depicted in Ivory Tower.

But an even more interesting criticism comes out of a book I’m finishing which will be the subject of next Monday’s column: Why Does College Cost So Much? which takes on the entire conventional wisdom that suffuses not just Ivory Tower but virtually every work that tries to lay responsibility onto someone (up to and including “the system”) for today’s crisis in higher education.

Leave a Reply