One of the things I’ve enjoyed most about plunging into the MOOC phenom is the willingness of those involved with it to listen to news both good and bad – both praise and criticism – with an open mind.

You have to understand that this experience is rather new, having worked in or with a number of companies during my professional career that required “Drinking the Kool-aid” (i.e., buying into someone else’s hype) in order to advance or close deals.

Beyond the disturbing fact of how quickly a phrase with such an origin turned into common Business-speak, treating criticism as a form of negativity or disloyalty always struck me as bordering on the suicidal. After all, can any of us (when not under pressure) really claim to have never worked for a company or sold a product that could not stand significant improvement? And in this era of rapid change, even great ideas and successful strategies need constant honest appraisal, lest they harden into dogma.

Perhaps it is the engineering mindset that suffuses the current generation of MOOC enthusiasts which makes those involved with this project open to suggestions (since they offer the opportunity for endless tinkering with “the platform”). But I suspect that this dynamic is really just another manifestation of the experimental nature of online learning, with “experiment” being a code word for a series of projects and products being brought to market with full understanding of how far they fall from perfection.

This dynamic was brought home to me during a panel discussion on MOOCs put on at this week’s LINC conference at MIT.

At the table were two unwavering champions of MOOCs in general, and MIT’s own MOOCs in particular (edX President Anant Agarwal and Sanjay Sarma, the Director of MIT’s Office of Digital Learning). But the other two panel members (Tony Bates, a Research Associate from Ontario’s successful Distance Education and Training Network, and Sir John Daniel, a long-time leader in Open Learning) pulled no punches in their critique of the most recent massive online courses.

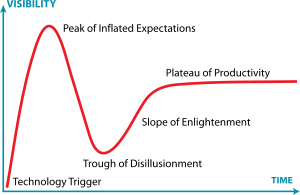

Daniel in particular took delight in plugging MOOC excitement into “The Hype Cycle” (illustrated below) a staple PowerPoint image that maps newsworthy technologies into a timeline that involves initial Inflated Expectations, followed by Disillusionment, after which more sober Enlightenment leads to ultimate Productivity.

If you assume MOOCs to be following this trajectory, then all the ink that’s been spilled about them over the last 12-24 months is part of that initial steep curve of inflated expectation with recent negative stories representing the start of a disillusionment trend that will ultimately bottom out, after which a more realistic mindset will take over which will lead to slow, steady growth as MOOCs find their proper, productive place in a wider constellation of options for free learning.

For Daniel (and other critics), the lack of any clear direction for turning MOOC education into college credit limits their ability to truly revolutionize education. And for those who grew up in (or helped create) earlier distance learning predicated on giving students new options for obtaining a degree, new technologies that throw classes open to the world without a clear pathway of what happens next can seem slightly cracked.

But as I discussed previously, one of the least talked about but most significant aspects of the MOOC “revolution” is what it means as a cultural phenomenon.

For even just a few years ago, the best known colleges assumed their classes to be prized assets that needed to be secured lest they fall into the hands of people outside the ivied bunker. Given that, consider what it means that today those same colleges are measuring their prestige on how widely they are willing to share (rather than hoard) those same assets.

And once sharing and openness become points of pride, it’s difficult to return to a state of possessiveness without coming off as selfish or – even more dreadful – “behind the times.”

So just as the developers of the platforms behind edX, Coursera and Udacity are not going to erase their code or pulp their servers if everything goes wrong, new ways for colleges to interact with the public will not go away even if MOOCs do end up going through a period of Hype Curve realignment.

But to keep the periods between over-enthusiasm, over-cynicism and productivity as short as possible, we need to continue one of the most important aspects of this latest EdTech trend: the readiness to listen to those who, while not claiming the emperor has no clothes, are happy to point out when he could stand to change his shirt.

Supply and demand.

Demand today is college at fair cost to parents of millions .

That means degrees.

Somehow that is being solved.

First 10 state universities bought online courses from Coursera at $ 36 per course to provide credits and degrees to their students covering 1.25 million students.

Now 15 provosts ( Uni of Illinois, Uni of Michigan, Purdue, ….) are working on SHARING online courses for developing and disseminating .

California is working on buying MOOCs for their 4 million CCs + CSU + UC students .

State will force them .

I hope this will continue. But they should not split up to many pieces .

Most important point is the price.

Coursera price of $ 36 per course really revealed all the efficiency of MOOCs .

I claim the cost is really less than $ 1 . But Coursera price of $ 36 is not bad at this point either .